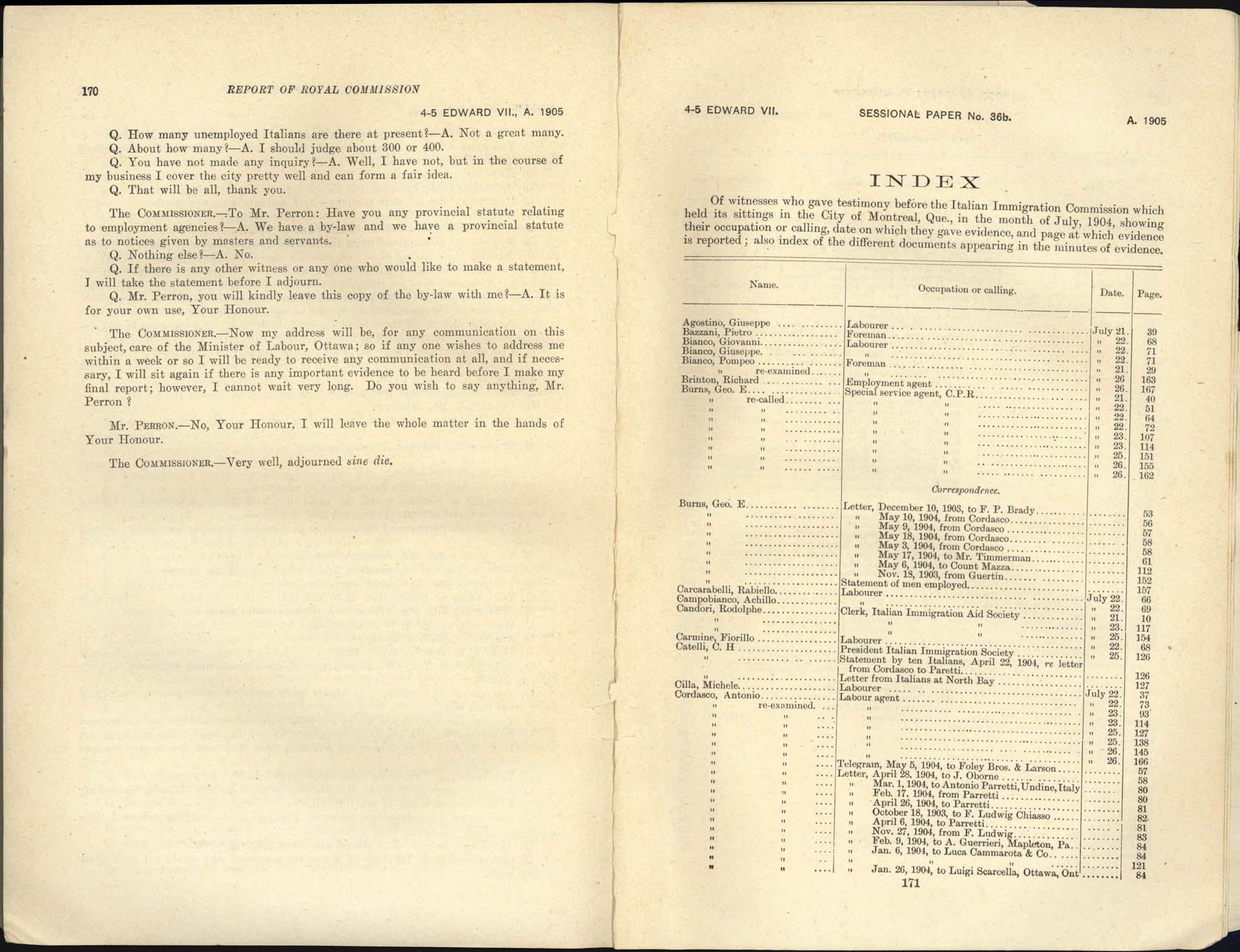

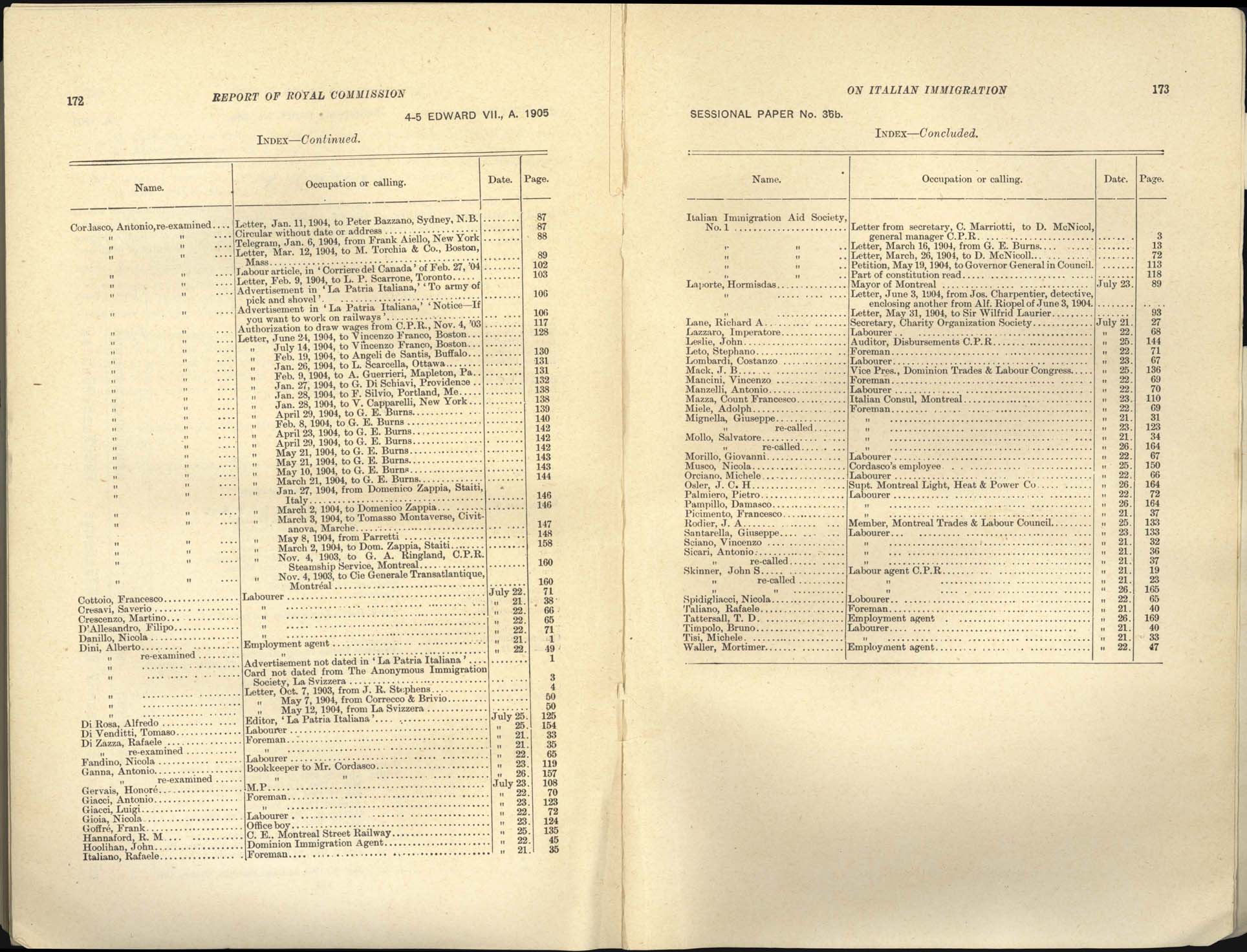

The Royal Commission Appointed to Inquire into the Immigration of Italian Labourers to Montreal and the Alleged Fraudulent Practices of Employment Agencies was called in 1904 to investigate the recent influx of Italian labourers to Montreal and their exploitation by immigration agents. There were at least 6,000 Italians in Montreal in May of 1904, many of them unemployed despite being promised immediate employment upon their arrival in Canada.

Large numbers of unskilled Italian labourers came to Canada at the beginning of the twentieth century, predominantly from the economically depressed regions of southern Italy. Although the government preferred agricultural immigrants, unskilled labourers were required to meet industrial demands. Italian migrants primarily went to Montreal and Toronto, finding work on the railway and in the mines. These labourers did not intend to stay in Canada but rather work for a season and make enough money to improve their economic situation in Italy. This system of sojourning labour was facilitated by padroni, Italian labour brokers that recruited Italian workers for Canadian employers and oversaw their transport and employment upon arriving in Canada. The system was rife with corruption as many padroni used deceptive tactics in the recruitment process and inflated fees for brokerage, transportation and food supply.[1]

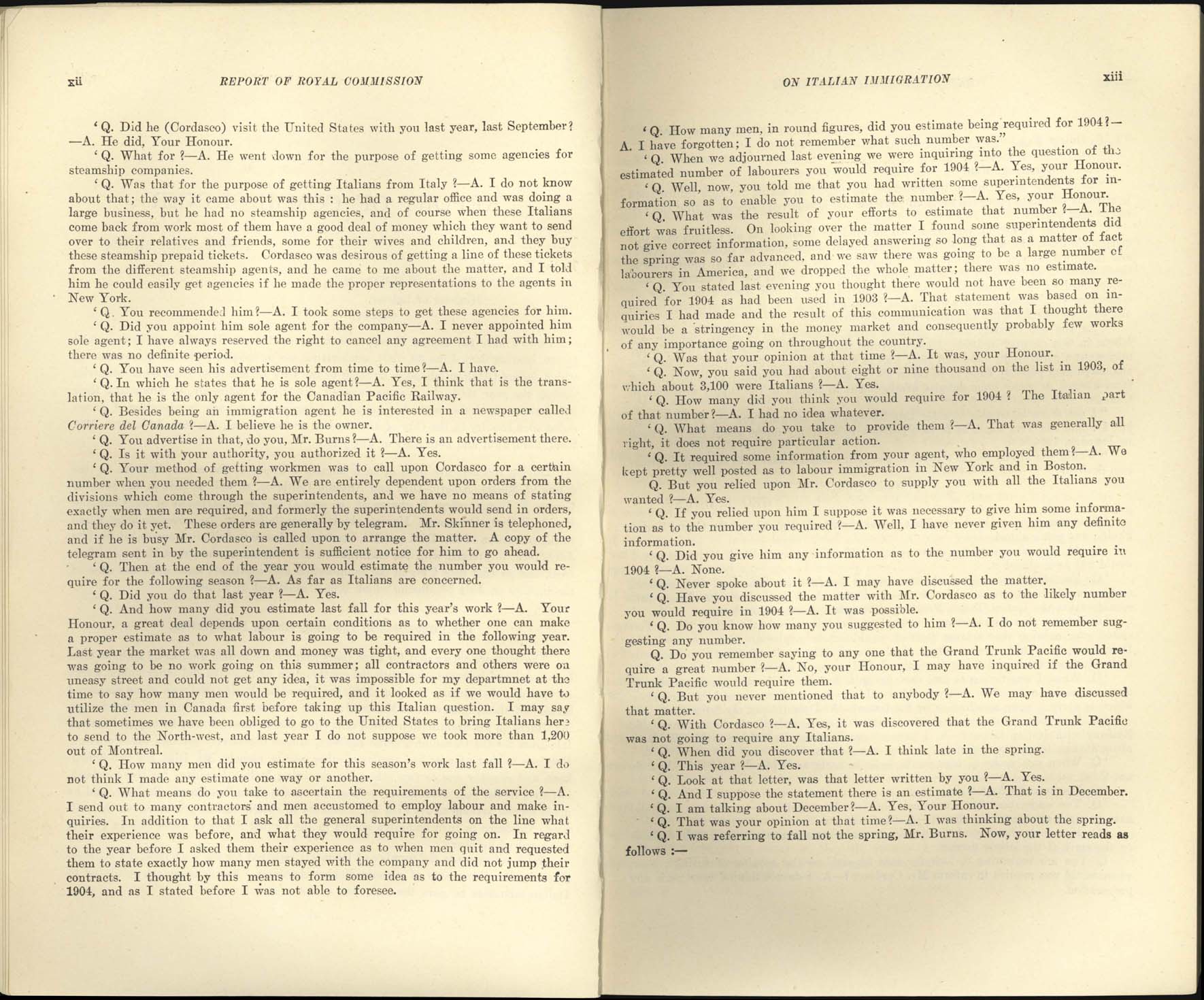

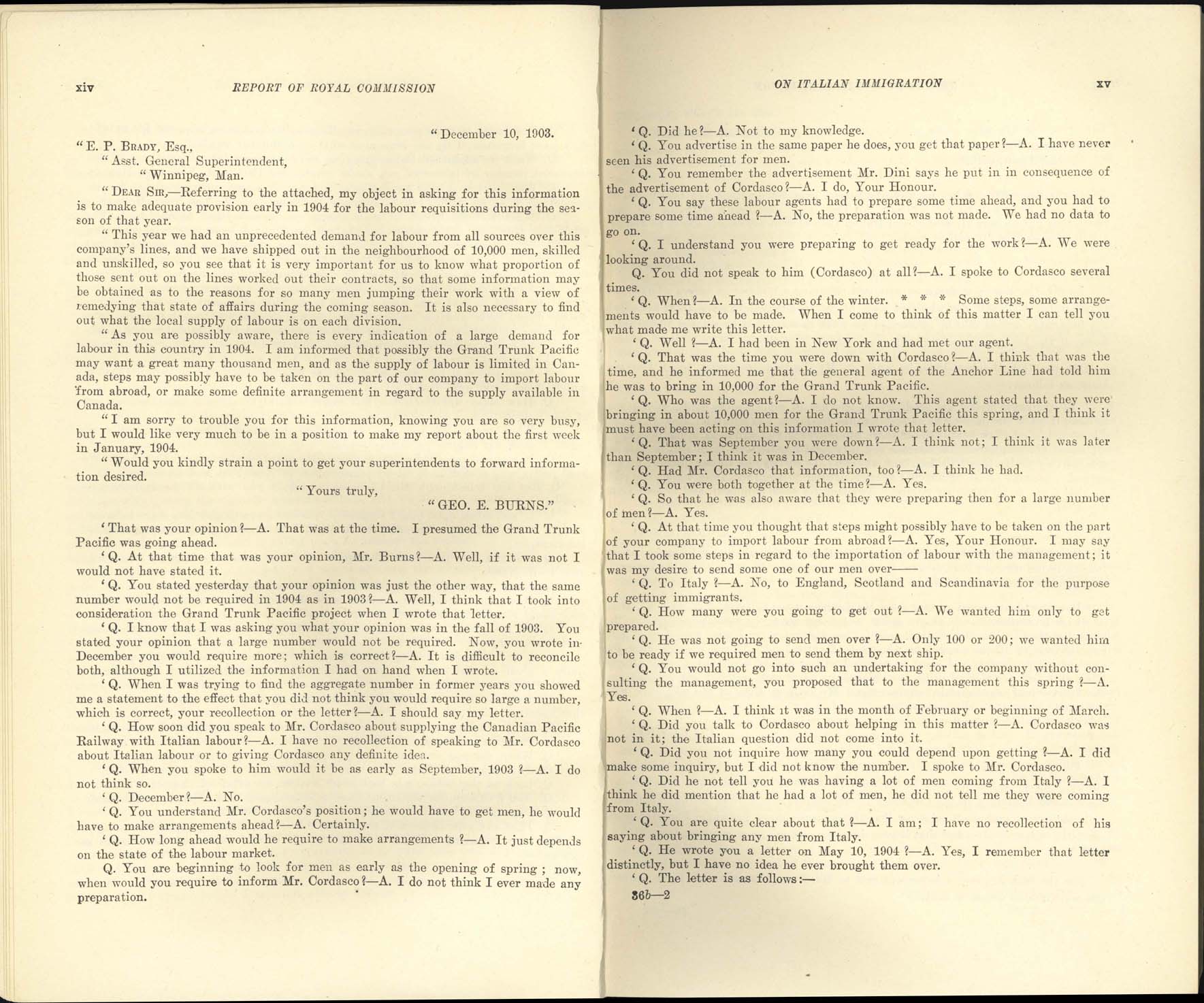

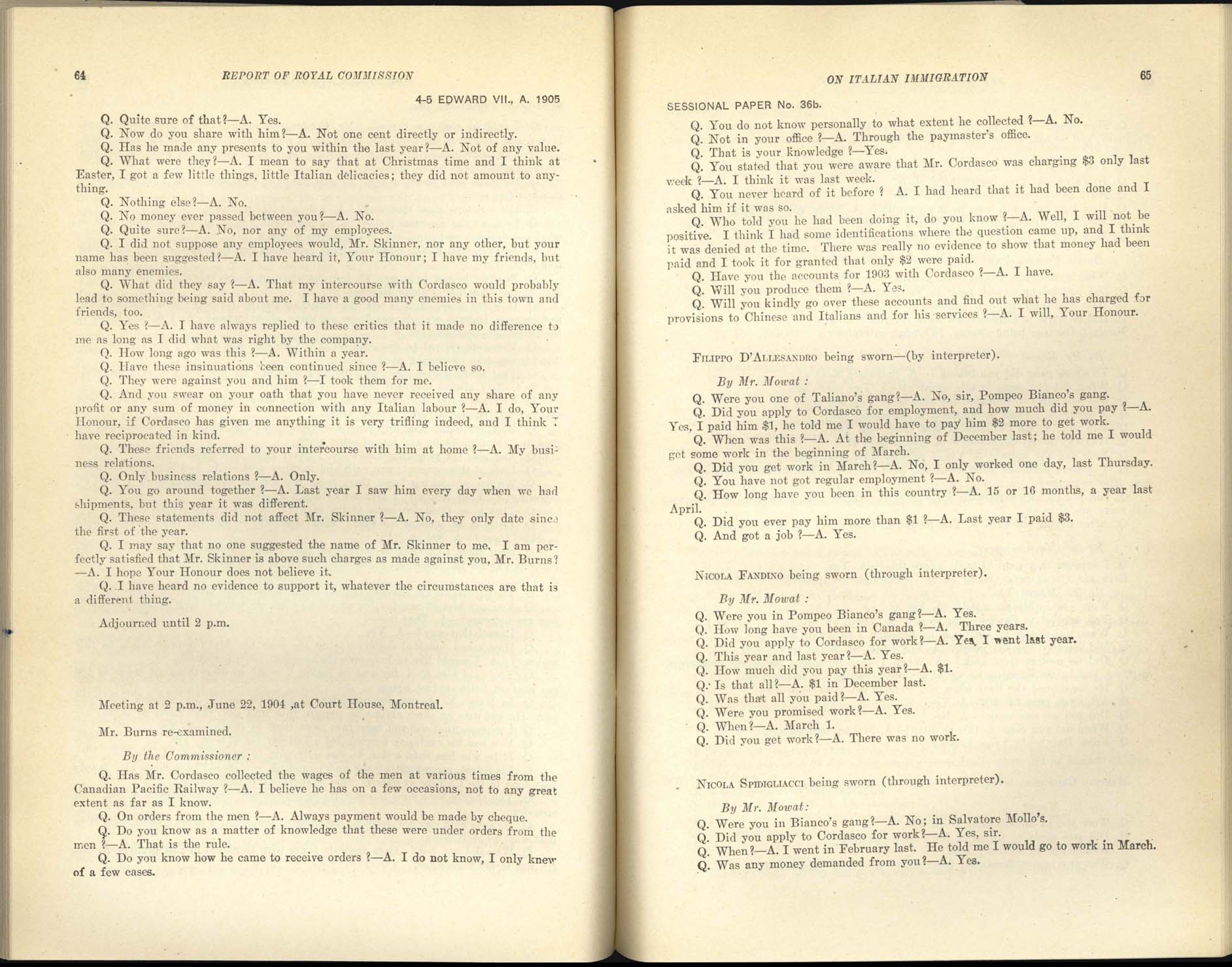

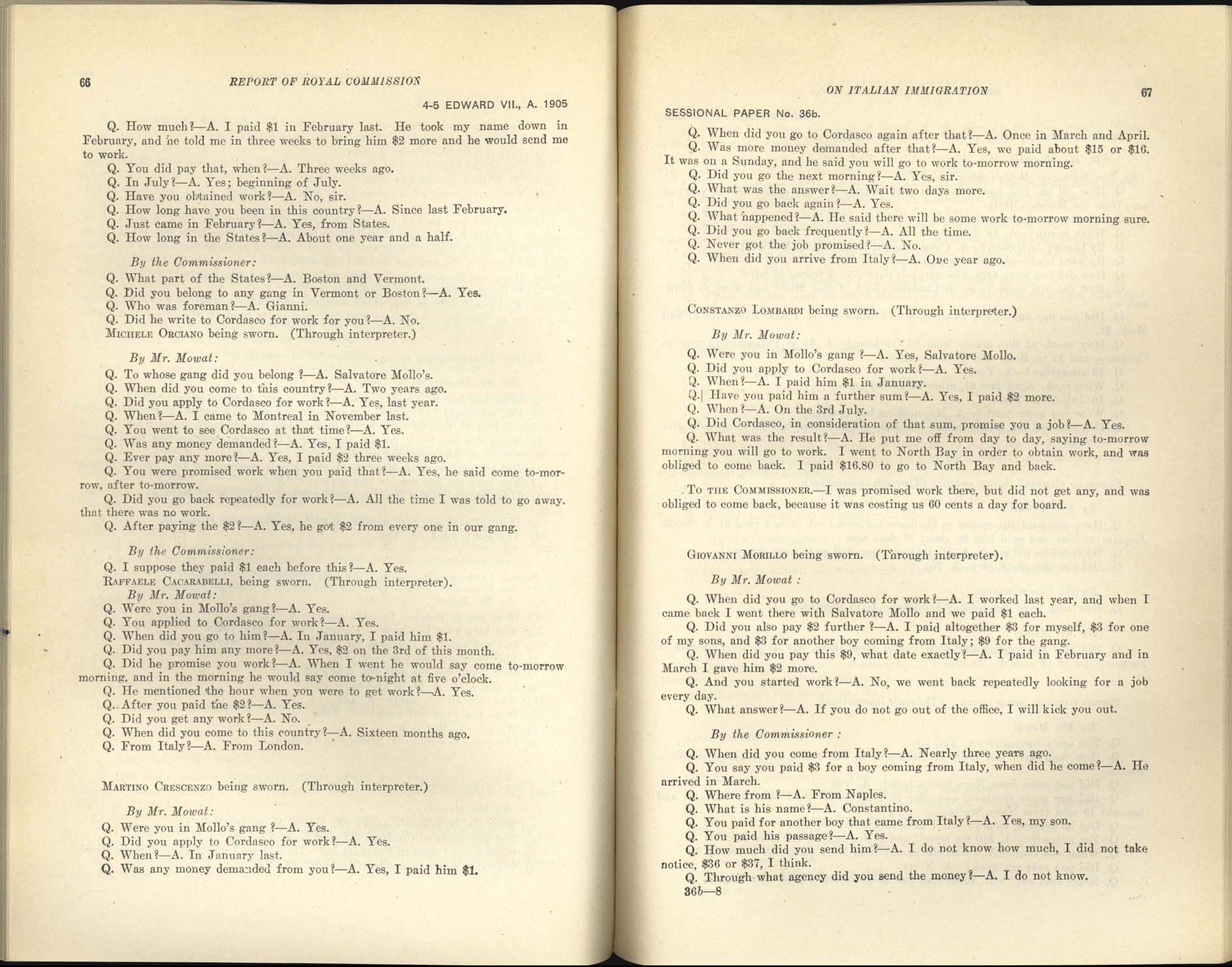

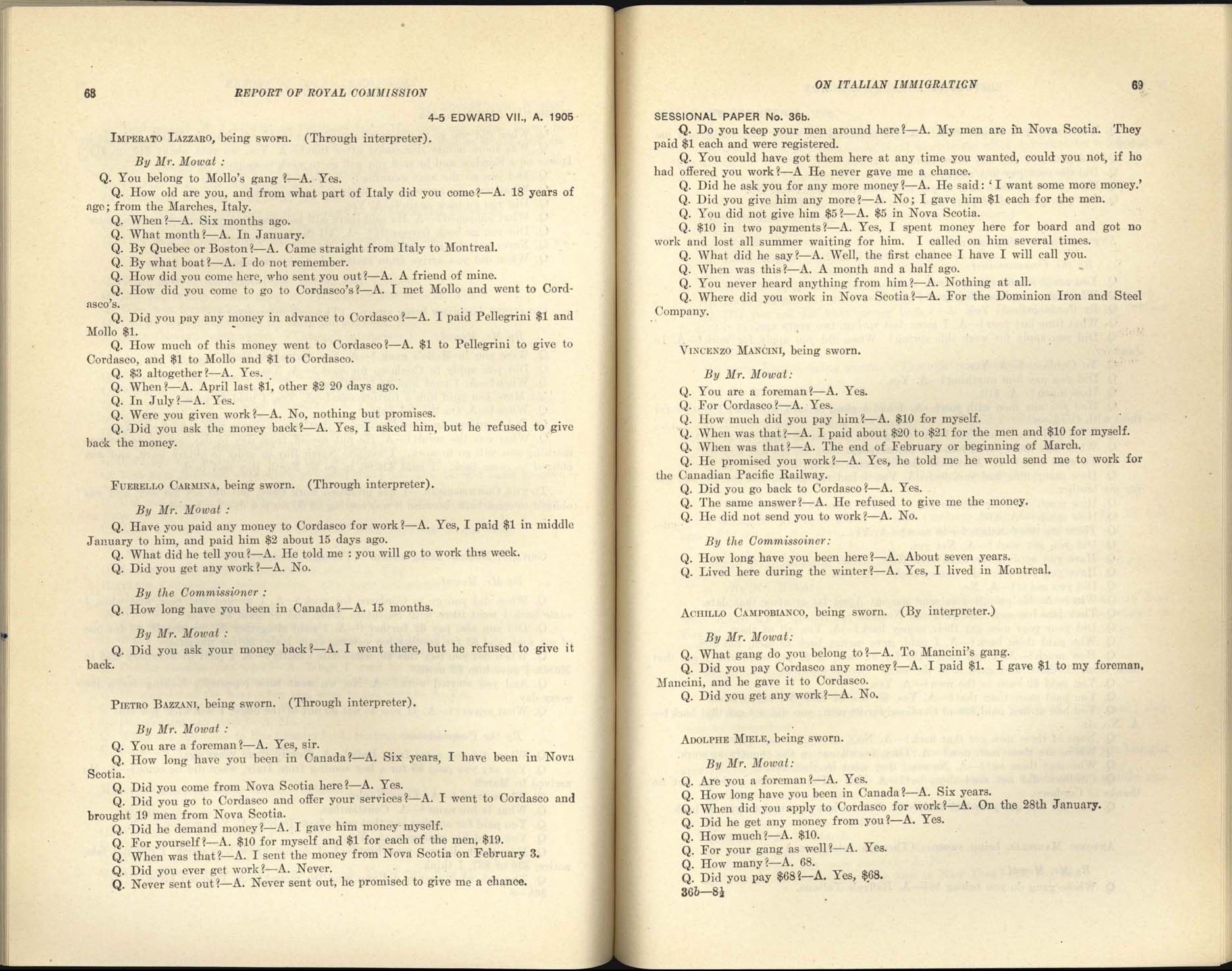

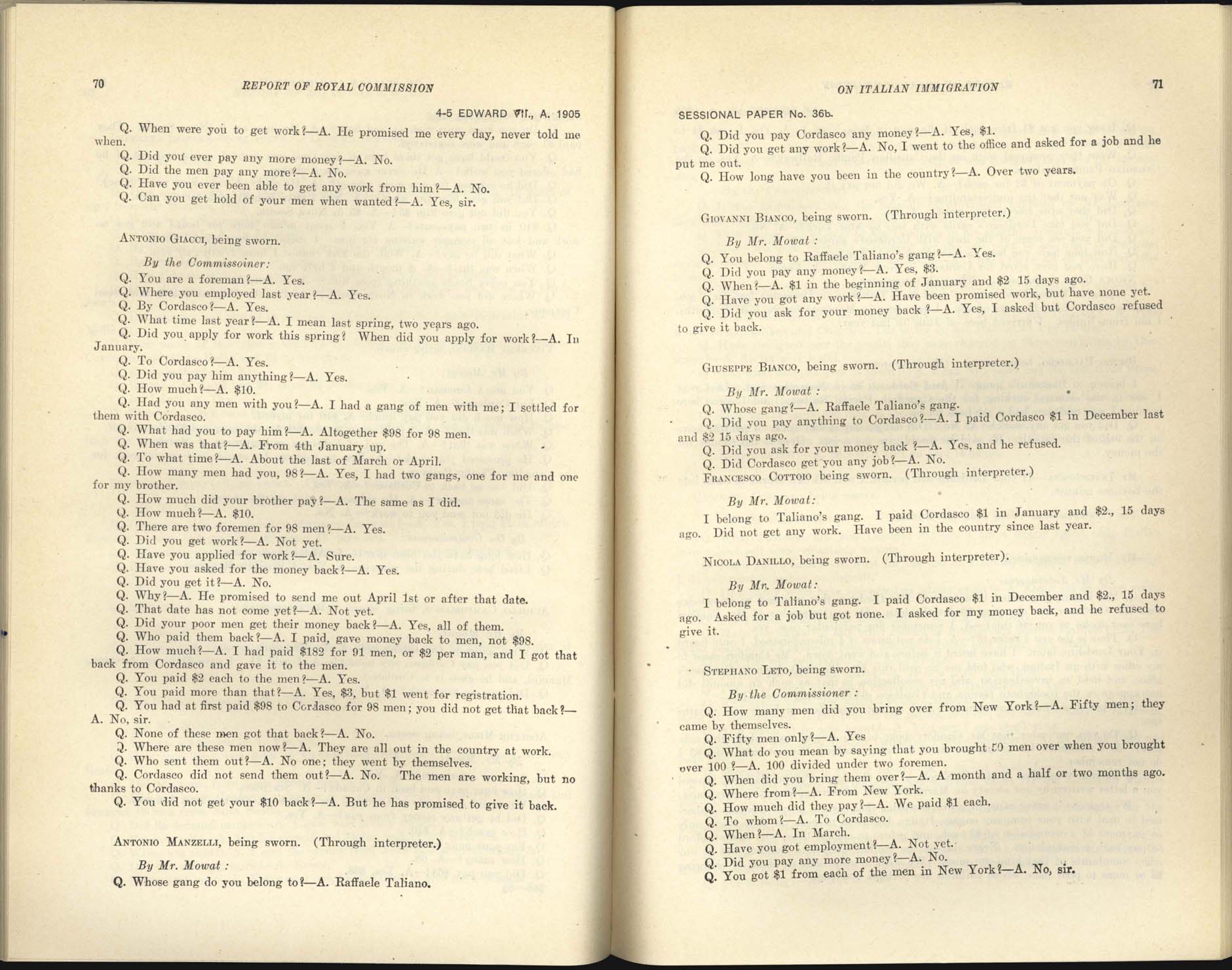

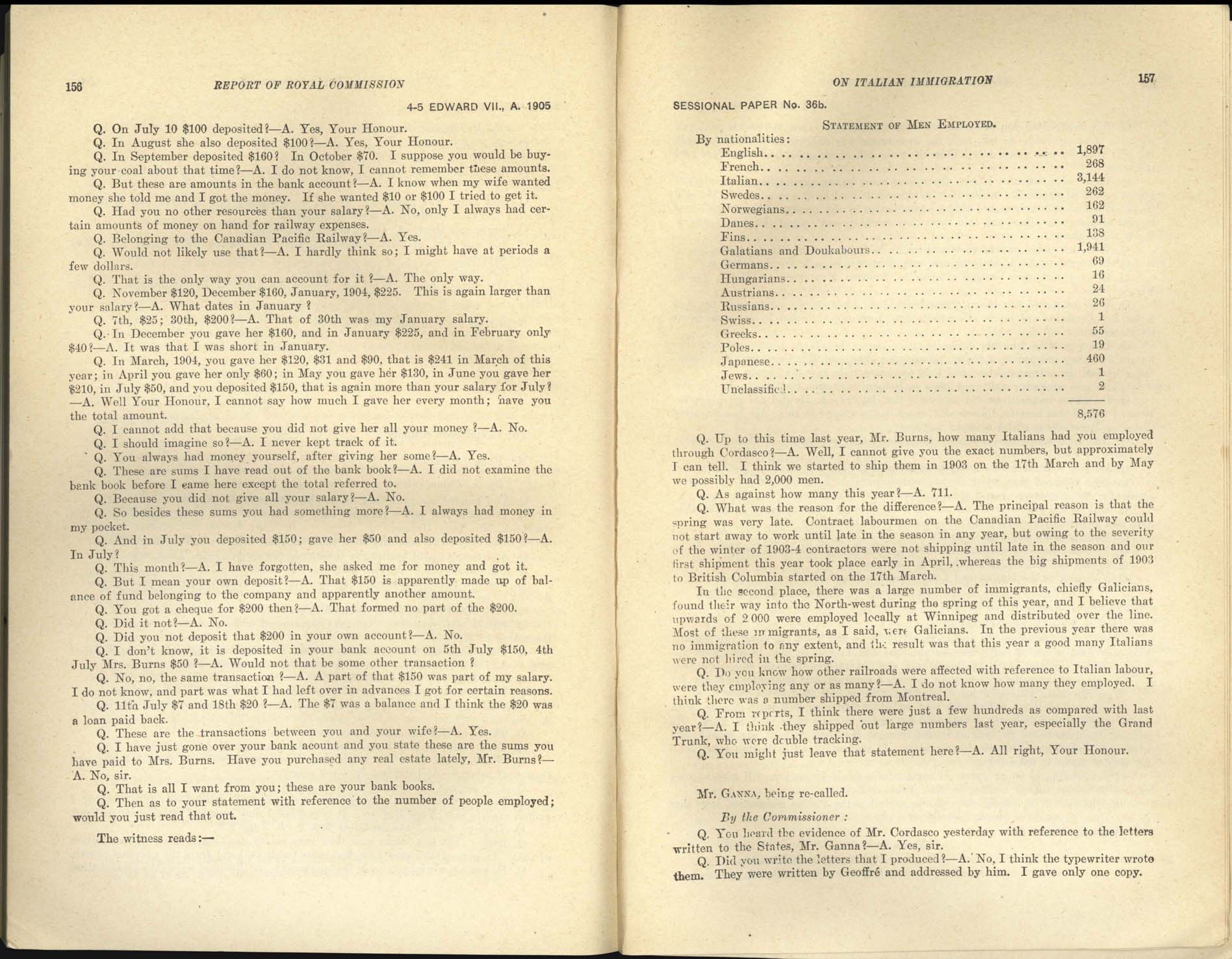

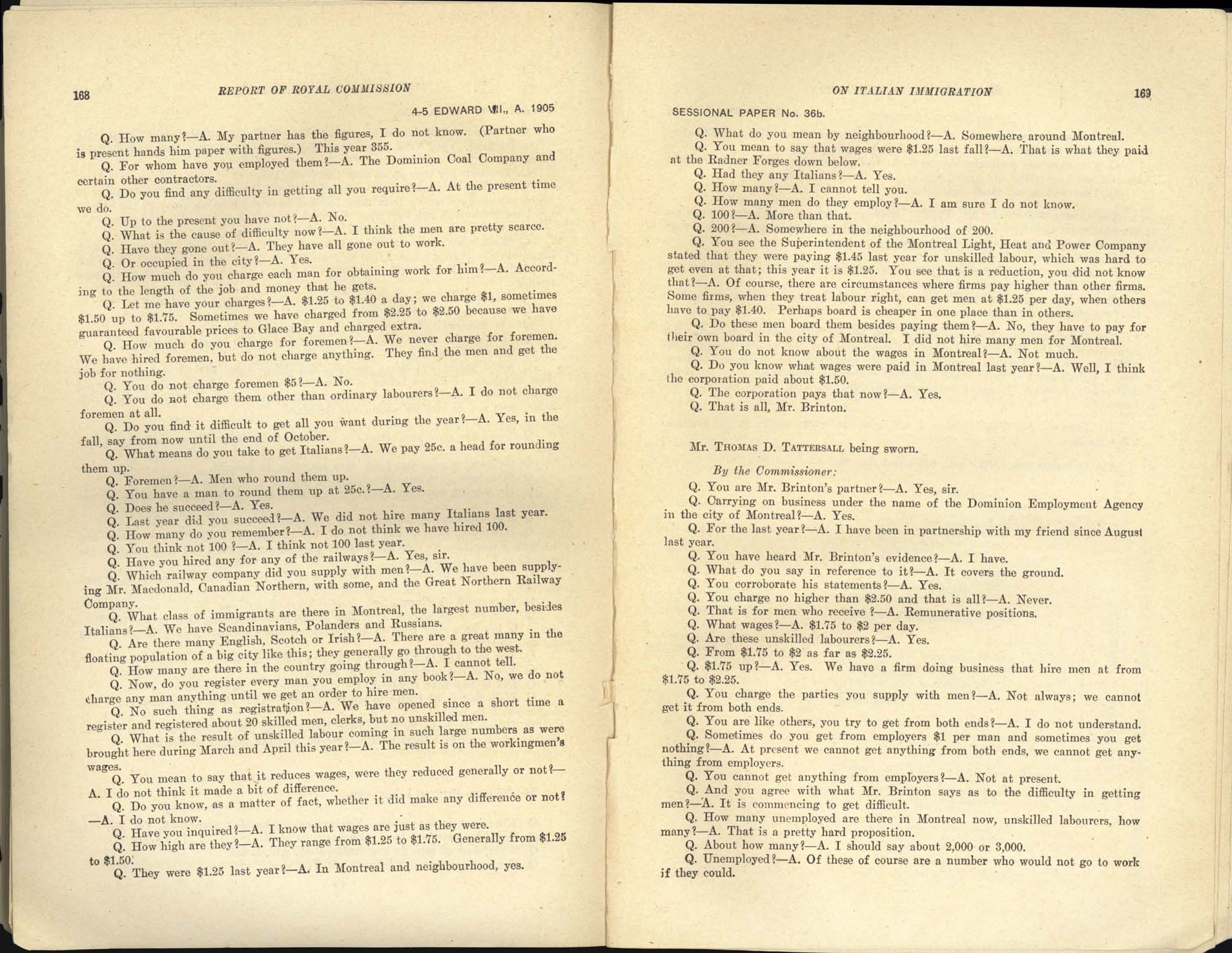

The commission, led by Judge John Winchester, conducted an in depth examination of the padrone system, focusing its investigation on prominent Montreal padrone Antonio Cordasco. Since 1901, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) had engaged Italian labourers almost exclusively through Cordasco. Witnesses alleged that Italian labourers could not obtain work with the CPR until they paid Cordasco a fee for arranging their employment. Once the labourers were hired, additional charges for supplies and food were deducted from their wages and paid directly to Cordasco. The rates Cordasco charged were 60 to 150 percent above cost.[2]

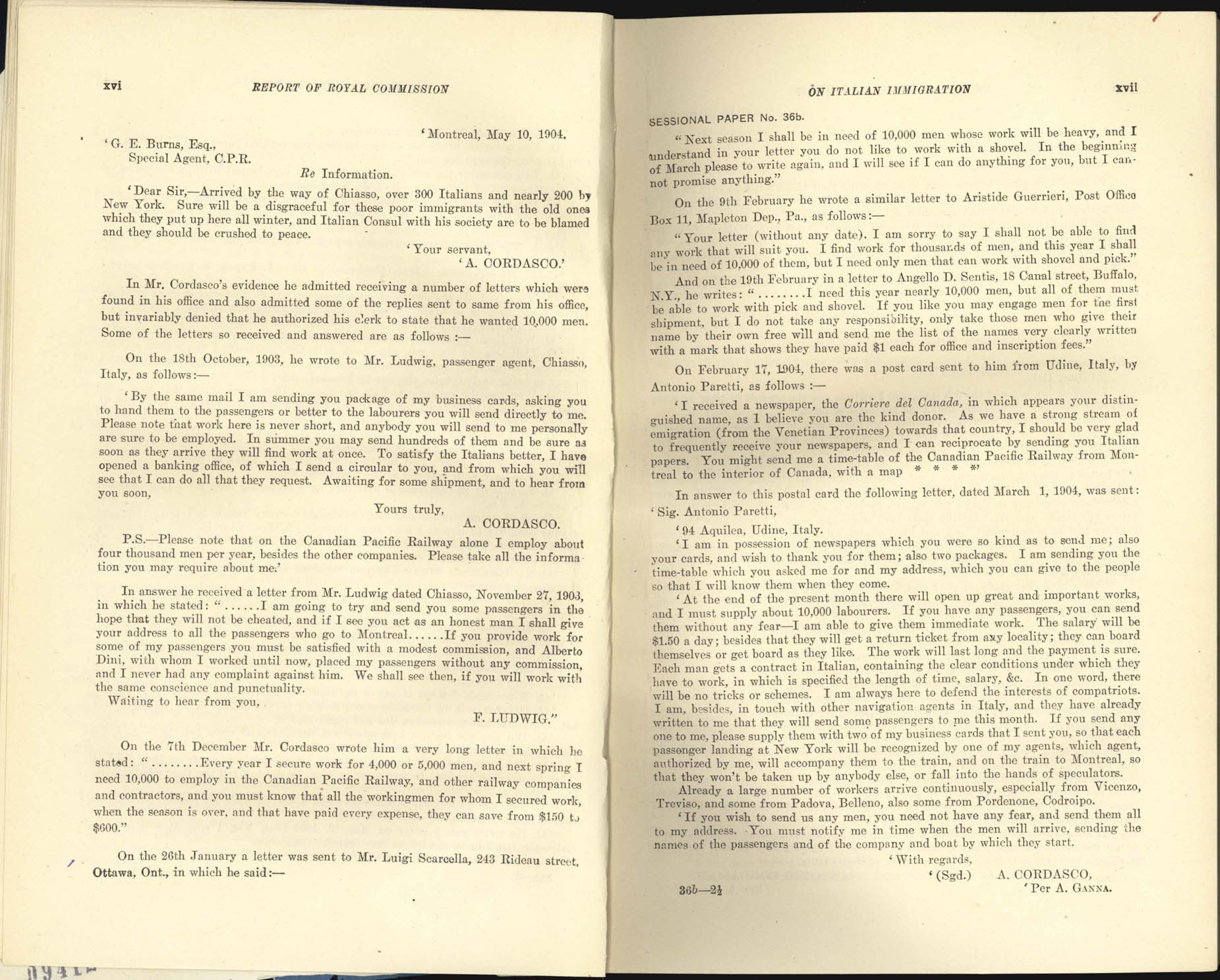

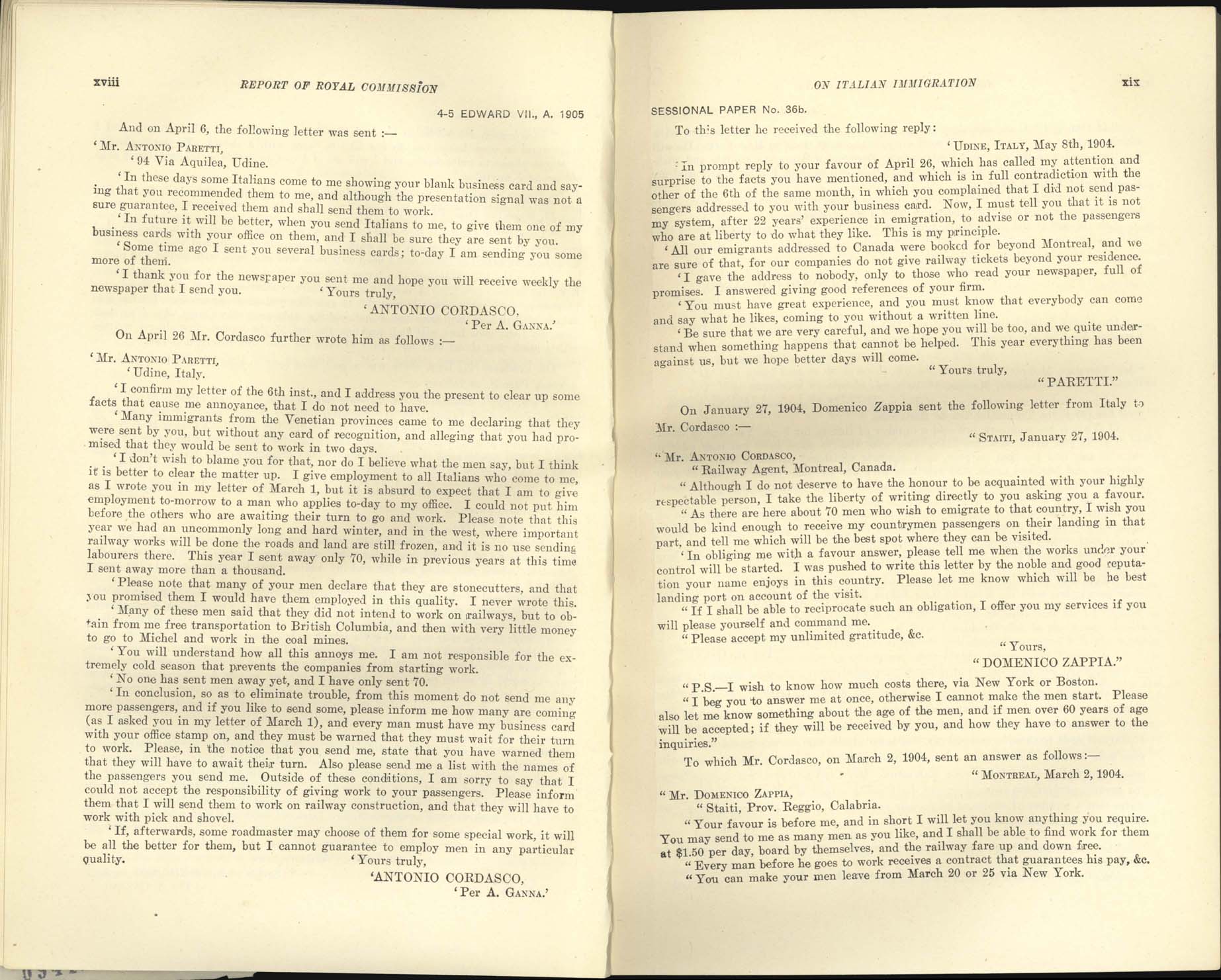

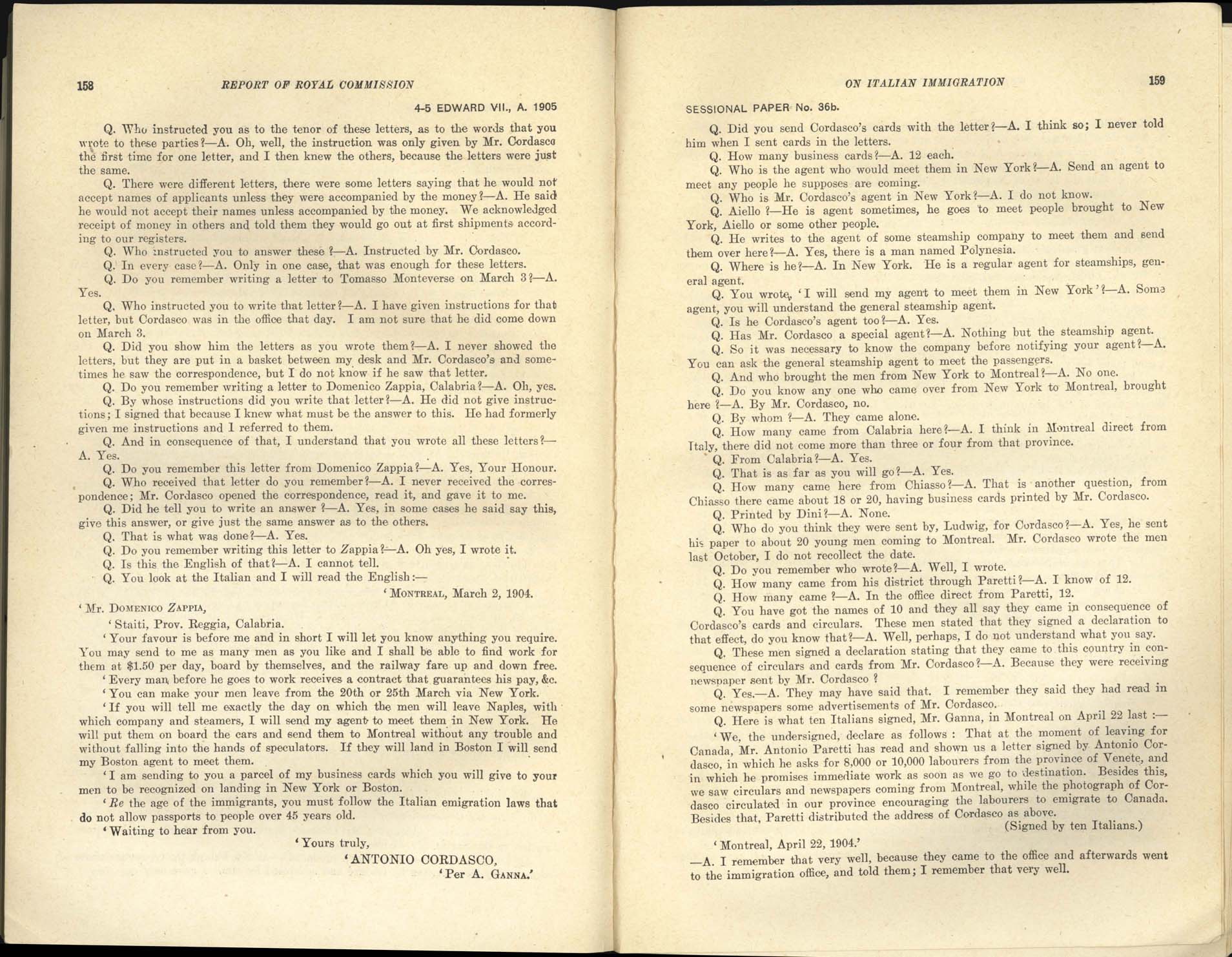

Cordasco induced Italian labourers to come to Canada by taking out advertisements in Italian-Canadian newspapers circulated in Italy, promising immediate employment upon arriving in Canada. In 1904, Cordasco recruited more men than the CPR required, creating an influx of unemployed Italian labourers in Montreal. Although Cordasco was aware of the labour surplus, he continued to demand fees from newly arrived Italian migrants under the false pretense of finding them employment.

In his final report, Judge Winchester recommended that the city of Montreal pass a by-law requiring immigration agents and offices to be licensed before being permitted to carry out their business. Following the conclusion of the commission, the CPR fired Cordasco as their Italian labour agent.[3] Although the commission effectively ended Cordasco’s career as a padrone, the system as a whole remained intact. The major companies employing Italian sojourners continued to use padroni to obtain cheap Italian labour.[4]

Library and Archives Canada. The Royal Commission Appointed to Inquire into the Immigration of Italian Labourers to Montreal and the Alleged Fraudulent Practices of Employment Agencies. Report of Commissioner and Evidence, 1904-1905.

- Ninette Kelley and Michael Trebilcock, The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998), 139-140.

- Gunther Peck, “Reinventing Free Labor: Immigrant Padrones and Contract Laborers in North America, 1885-1925,” The Journal of American History 83, no. 3 (December 1996): 858.

- Peck, 866.

- Robert F. Harney,“Montreal's King of Italian Labour: A Case Study of Padronism,” Labour / Le Travail 4 (1979): 81.