by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

(Updated September 28, 2020)

Introduction: Adolescent Impressions of Immigrating to Canada

An often overlooked aspect of Pier 21’s site history is the immigration experience of children. Young newcomers are frequently mentioned in relation to the immigration process and the role of the Canadian state in processing immigrants. Similarly, the efforts of voluntary service agencies including the Red Cross and its nursery, were instrumental in caring for young children as their parents used Pier 21’s amenities to rest, take a shower, secure food, or purchase tickets for train travel to their final destination across Canada. Whether they arrived as immigrants or refugees by way of family reunification, private sponsorship, or government-assisted program, their experiences shared similarities, but were also unique to the process of arrival. Below are impressions of arrival and the immigration process of four adolescents through Pier 21: Margaret Beal (Britain), Jackie Solski (Poland), Angelina Crosdale (Italy), and Bassam Nahas (Lebanon).[1] They illustrate the fears and hopes, and frustrations and joys of continuing their lives in Canada.

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (DI2014.457.1)

“…unlike anything we had seen up to that time” - Margaret Beal, 14 years old, Britain

In August 1940, British evacuee child Margaret Beal, boarded a train for Greenock before embarking on RMS Antonia for its transatlantic voyage to Halifax. As one of 1,532 children brought to Canada under the auspices of the Children’s Overseas Reception Board (CORB), Beal recalls that the ship travelled as part of a convoy for protection. As an older child evacuee, she – along with others – was put in charge of a group of fifteen children as ‘helpers.’ She remembers practicing a lifeboat drill, carrying a gas mask, and having to sleep in her clothes for several days. On 19 August, the vessel carrying Beal and her companions landed at Halifax.

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (R2014.458.39)

Given the wartime circumstances and the uniqueness of this movement of children to Canada, local media paid particular attention to the arrival of the British evacuee children. Beal remembers a newsreel camera crew came aboard RMS Antonia and filmed the evacuee children. Afterwards, the group quickly disembarked from the ship and boarded a train “…which was unlike anything we had seen up to that time. In the UK in those days one generally sat in a ‘carriage’ which held six people, three sitting on either side facing one another…by contrast we were in coaches much like the ones seen today, and the seats made into beds for sleeping.” Beal found the journey by train rather slow since it had to stop at many stations across Canada. With every stop, she and her fellow travellers found that individuals were aware of their forthcoming arrival and ready to ask questions about the war and life in Britain. Beal eventually got off the train and started a new life in Winnipeg.

“Tears running down our faces, seeing all these people getting on their trains and...we were here for three months.” - Jackie Solski, 11 years old, Poland

In March 1950, Jackie Solski landed at Pier 21 with her parents, sister, and brother aboard USS General W.C. Langfitt. Upon disembarking from the ship, the Jewish refugee family from Poland was given tags to help officials and volunteers guide them to the proper train for the final leg of their journey. Solski recalls her family was penniless upon their arrival in Canada. Solski and the rest of her family went through their civil interview and medical examination only to have her brother’s fever prevent them from leaving the immigration facility. They were subsequently detained and placed in Pier 21’s detention quarters for three months until Solski’s brother recovered from a fever that Canadian officers later described as strep throat. Solski remembers that “…every morning they would open the door and let us out and every night, I think eight o’clock or nine o’clock, they would lock the doors. And our room faced the railroad tracks and my sister and my mother and I would look, I’m not joking, we would be like this. Tears running down our faces, seeing all these people getting on their trains and going and we were still there. And we were here for three months.”

Solski later discovered that her brother’s diagnosis of strep throat was politically motivated. Under suspicion of maintaining links to the communist movement in Canada, the family was held in detention until their political allegiances could be determined. Solski’s parents were social democrats, who had never been involved in the communist movement in Poland. The family’s immigration to Canada was sponsored by Solski’s uncle and aunt. Her uncle had at one time been a member of the Communist Party in Canada, although he did not attend meetings or participate in any organized activities. With the help of David Lewis, a prominent labour lawyer and national secretary of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), the family was eventually able to depart Pier 21 for their final destination of Toronto.

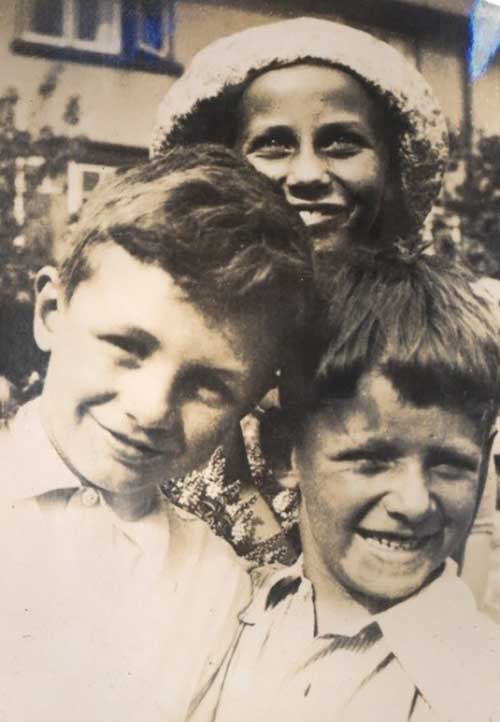

“I don't want to live in this new place because I hate the bread.” - Angelina Crosdale, 8 years old, Italy

In 1959, eight-year-old Angelina Crosdale (née Marchitto) left her homeland of Italy for Canada. In Naples, she boarded a vessel with her father and two-year-old sister. The transatlantic crossing took a toll on the family, with Crosdale’s father becoming seasick and bedridden, while she was forced to seek out meals for herself and her sister in the ship dining hall. Crosdale recalls a steward bringing the family a large amount of sandwiches and fruit. For most of the week-long journey, she stayed in the family’s cabin and ate lots of oranges. Upon landing in Halifax, Crosdale remembers that there were many fellow travellers in the immigration facility, giving the young girl from a small town in Italy the impression that thousands of individuals were arriving in Canada at once. While her father filled out immigration forms, Crosdale and her sister sat with their trunks for what seemed like a long period of time. Her father later took his two daughters to a small kiosk to purchase food. Not yet able to speak English, Crosdale’s father bought a loaf of white sliced bread. Crosdale, who was hungry, bit into the bread to discover that it was “sweet, soft and it stuck to my palate. It was awful!” Being used to a different style of bread, Crosdale remembers vividly that she cried and told her father “I don’t want to live in this new place because I hate the bread.”

Before the family could continue its journey to Montreal, they had to first go through customs inspection at Pier 21 in Halifax. There, Crosdale’s father claimed clothing and bedding – two large bags of sheep’s wool in order to create mattresses or weave blankets. Following her father’s declaration, in Italian and translated through an interpreter, a customs officer asked whether he had any meats in his possession. Recognizing that the family had come from Italy, where previous immigrants had attempted to enter Canada with various meats including prosciutto, salami, and sausages, customs officers searched the family’s belongings only to discover a small cloth bag of flour, which a neighbour had given the family to bring to a relative in Montreal as a gift. Indicting the flour was cornmeal, Crosdale’s father was unaware that the neighbour had hidden a chunk of homemade pork sausage inside. As a result of finding contraband, customs officers subsequently inspected every item in both trunks. Both pieces of luggage contained walnuts placed by Crosdale’s grandmother into small areas where there was remaining space…

I can see it as clearly as it was yesterday: as the officers would remove more items from the trunks in search of some contraband meat, there was a cascade of walnuts from the trunk onto the polished floor. My sister and I would try as fast as possible to scoop them up or chase them down before they came underfoot of the rest of the multitude at Pier 21. I know that we did not pick all those walnuts up and after the officers were through (they found nothing else) my father was too tired and disgusted to worry about walnuts. To this day, I wonder how many people enjoyed my grandmother's walnuts.

With her father and younger sister, Angelina Crosdale eventually boarded a train for Montreal where her uncle, aunt, and cousins were awaiting their arrival.

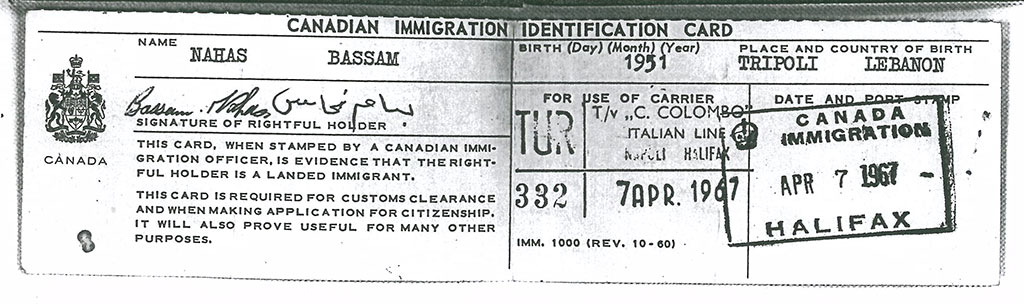

“They said, oh, you better be prepared. Take some wool with you. You’re going to freeze to death.” - Bassam Nahas, 15 years old, Lebanon

On 23 March 1967, fifteen-year-old Bassam Nahas boarded a vessel in Beirut for Naples, Italy with a stop in Port Said, Egypt. After four days, he arrived in Naples, where he transferred to a much larger vessel, SS Cristoforo Columbo. Unfortunately, he was unable to depart for Canada due to a worker’s strike. Eventually, the vessel and its passengers were able to leave the Italian port city. After a nine-day transatlantic voyage, Nahas arrived in Halifax on 7 April 1967. Upon landing at Pier 21, Nahas recalls seeing his older brother for the first time in many years…

I was so excited to meet the rest of my family, that I haven’t seen them for a little while. My older brother—I could see him and I just basically went under the rope and went to hug him, and they just said, no, stay back there—you have to go through custom [sic], and so on and so forth. So, uh, it was—it was an exciting moment and, we had so much luggage with us because everybody put the scare to us before we came. They said, oh, you better be prepared. Take some wool with you. You’re going to freeze to death. Take some, uh—uh, food from, uh, Lebanon, because of the different diet you have. From cracked wheat to—uh, we brought containers—practically boxes—of olives, uh—cans of olives and oil.

The food that Nahas brought to Canada from Lebanon was not only intended to sustain him, but was also meant for his close relatives who had resettled in the country years earlier: “I remember, uh, we had, uh, one whole box—wooden box—that had, uh, those—probably around thirty litres of oil each. We had six containers of those oil—olive oil, and, four containers of—of olives, uh, that were all home-made stuff, you know, for local people.” Nahas notes that during his arrival in Halifax, he was not asked by a customs officer whether he had anything to declare. Oftentimes, Canadian immigration and customs officials would ask questions to ascertain an individual’s identity, background, previous employment, familial status in Canada, and what items they were bringing into the country. In Nahas’s case, he remembers not being asked anything: “no, they didn’t even ask you any questions, you know, they, we didn’t even have to declare anything. You know, they don’t ask you any questions, if you bring in any money, or jewellery, or food, or anything. Like, we were in the darkness, basically. And if they did ask, probably we wouldn’t understand.” Nahas later expressed his gratitude for the patience provided to him by Pier 21 staff and the residents of Halifax since he had to get accustomed to the English language, local weather, and his surroundings.

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (DI2017.50.2)

Conclusion

These four experiences of arrival and process at Pier 21 taken from the museum’s oral history and story collections illustrate the diverse impressions held by adolescent immigrants upon landing in Halifax. In most cases, whether the journey or immigration process was easy or difficult, young immigrant or refugee newcomers remained grateful for the opportunity to continue their lives in Canada.

Search our collections online:

/search-our-online-collections

Share your story with us:

/share/share-your-story

- Immigration Story of Margaret Smolensky, Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 (hereafter CMI) Collection (S2012.377.1); Oral History with Jackie Eisen, 16 July 2003, CMI Collection (03.07.16JE); Immigration Story of Angelina Crosdale, CMI Collection (S2012.737.1); Oral History with Bassam Nahas, 1 February 2012, CMI Collection (12.02.01BN).